Duck Development

Interesting times

When Jemima started visiting us we knew little about Mallards, or any other duck sort of duck for that matter. Apparently most domesticated ducks are derived from Mallards.

Jemima finding a way in 17th May 2020

No way through for waddlers 17th May 2020

I am sure there are reams and tomes of stuff about Mallard development and growth, and probably many learned papers, thesis and numerous PhD's awarded on the subject. Sadly, they are not all available to the lay person with a sudden duck infestation.

After her first visit we had learnt that they nest in hidden, sometimes ridiculous, places and can suddenly pop out with a family and expect access by foot power to places and routes they would normally fly, and that they may return the following year to the site they had previously successfully nested.

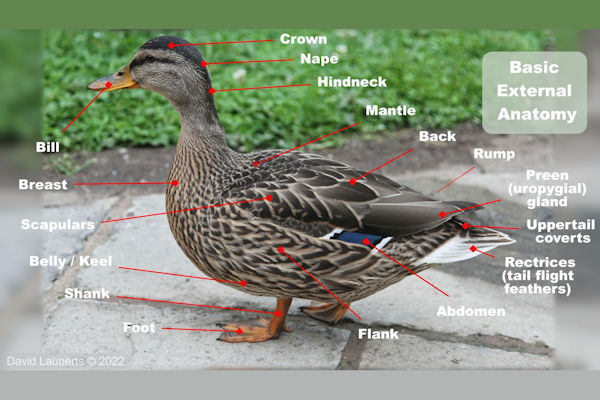

When she returned for the second time we used Google to prepare us for what may come. When Jemima arrived my knowledge of duck, or any bird, anatomy was restricted to head, beak, body, wings, and feet. A little research added a little more flavour.

I dare say some of what follows may not be what's in the books and in the minds of experts, but it comes from what we read, rightly or wrongly, in some place on the net and what we saw and noted. You can leave it and research it yourself or take it in the spirit it's offered in as some observations of a couple of rank amateur foster duckling keepers who found themselves having to learn things very quickly.

External Anatomy - Main Body

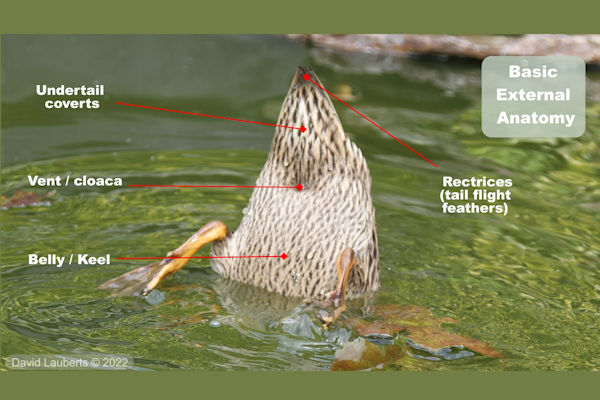

External Anatomy - Underside

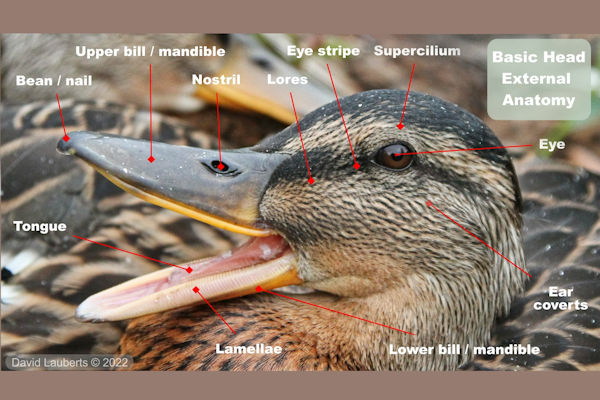

External Anatomy - Head

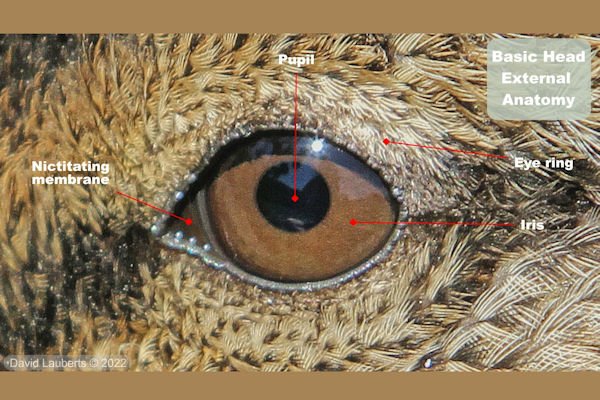

External Anatomy - Eye

I was going to say that feather function is all geared around flight, but it's not. There are flightless birds and the spectacular colour displays, camouflage and shaping for defence and display of some feathers we see in species and sexes belies that statement. There main purpose is to provide insulation to control body temperature and as structure that allows waterproofing.

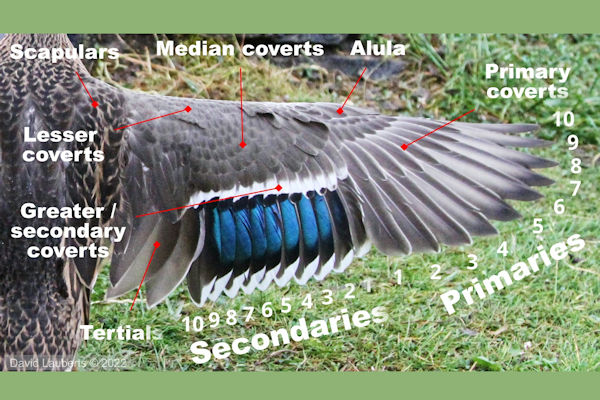

Nevertheless, feathers have a function in flight. Tertial feathers are the innermost flight feathers, attached to the 'upper arm' they contribute to flight but not as much as the secondary and primary feathers. There appears to be some debate on naming these feathers, tertial feathers attached to shoulder (brachial) area are not considered flight feathers but rather as protective covers for the feathers on the 'arm' and 'hand'.

The secondaries, attached to the 'forearms' give the main power and lift, the primaries attached to the 'hand' are the largest and furthest out and can be rotated to control direction and generate forward thrust during flight. The tail feathers (rectrices) help steer, balance, and control flight, giving the ability to reduce drag and act as a brake. The various other feathers can act as contour feathers to give the body and wings aerodynamic shape. It very interesting that there are very few muscles in wings themselves to save weight - the power for flight comes from the chest muscles acting on the arms with tendons stretching through the wing. They all act together to achieve the purpose of directed and controlled flight.

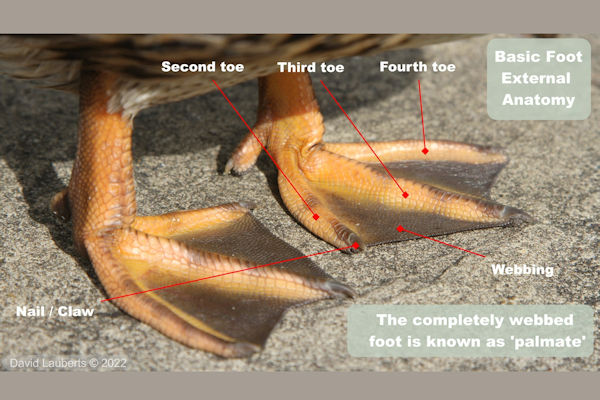

External Anatomy - Feet

External Anatomy - Wing

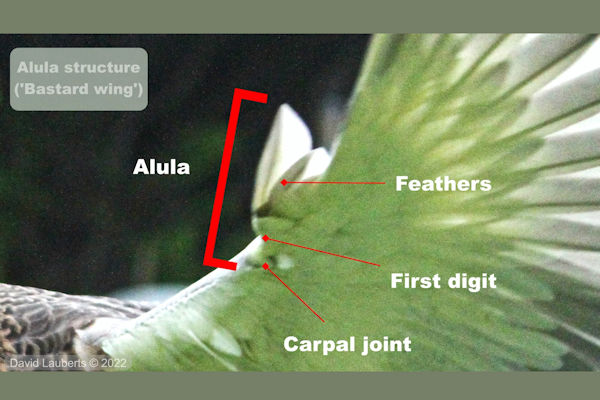

External Anatomy - Aula structure

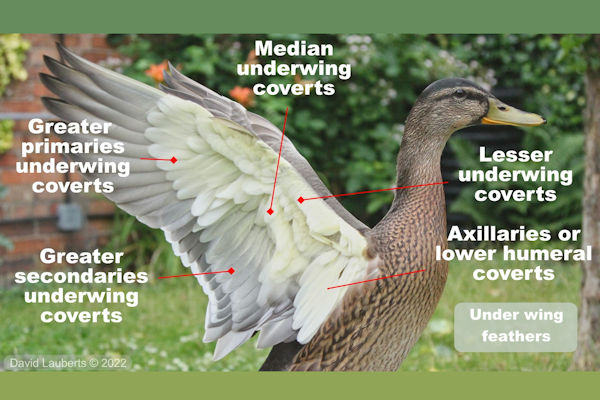

External Anatomy - Underwing

First 2021 sighting of Jemima 10am 26th Feb 2021

Dad looking for Jemima 8:48am 5th May 2021

Breeding and Nesting

Mallards usually pair for breeding in October / November, quite a long time before mating and egg laying in the following March /April. They are generally seasonally monogamous, that is the pairing lasts till egg laying is complete. In subsequent years both ducks find new mates for the new breeding season. In our case the relationship lasted well into the incubation period once the eggs were laid. This is apparently normal in case the female (the 'hen') has to abandon her first clutch of eggs and needs to start over again in a new nest and lay another clutch of eggs. The male (the 'drake') is then immediately available to mate and fertilise the eggs for the new clutch.

One interesting observation was the fact we are sure we saw the drake looking for Jemima a full month after he had last seen her after she was killed, and 2 weeks after the ducklings had hatched. It seems a bit random for another adult mallard drake to be hanging about, obviously looking down on Jemima's nesting site, in the middle of a built-up urban area away from the ponds, rivers and canals they inhabit round here unless it was one that knew where it was.

Diving into the hedge 6th March 2021

Jemima's nest on the wall March 2021

The hen selects the nesting site and builds the nest. She will return to the the site of the previous year's successful nesting, or (so we read with some trepidation) the area where the hen was hatched and raised. The drake just tags along for the ride.

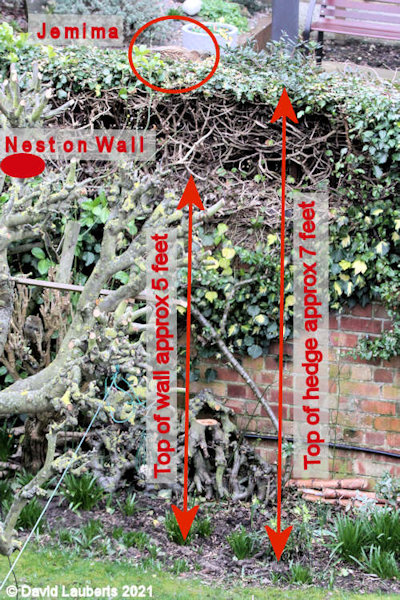

In our case Jemima started scouting her 2021 nesting site in our garden in late February with her drake, who certainly looked pretty bored by the whole process. The final decision did not seem to be made until the first week in March, once again choosing a spot 5 foot up on top of a wall in amongst ivy and thorn. We assume this was where she nested the year before, unbeknown to us. She would enter by dropping down through the hedge to the top of the wall but leave by going sideways out the hedge. They returned most days for a short while, both usually landing in the pond. She would inspect the nest site, possibly adding bits of twig and leaves that were hanging about on the wall. The drake just hung around the garden and pond looking bored and pretending that we couldn't see him.

Laying eggs

We first noticed her laying eggs on the 14th March. There were two. We don't know if he had laid two or one was from a previous visit and she had hidden it from our camera.

Mallard Egg

She would come every day, usually early in the morning and usually with her partner. They would usually land on the pond, after a quick look round she would fly up to the top of the hedge, look round again and dive into the greenery and down to her nest.

Once her egg was laid, she would rest a short while, cover her eggs with what she could find round her, and exit the nest sideways through the hedge.

She would either spend a very short time on our pond and then fly or fly off immediately until the next day.

Jemima's eggs in the nest

Depending on what you read Mallards may lay an egg ever day or every other day. In our case it seems like she laid one almost every day.

It seems quite a miracle to me that eventually all the eggs seem to hatch at once. Not sure of the science behind it but the fertilised eggs obviously stay in some sort of limbo state till the hen has finished laying all the eggs she is ready to lay. The literature we read says mallards lay between 8 and 13 eggs. Jemima laid 14 that we found. The colour of the eggs was very pale green/light blue.

13 days later on the 27th March we noticed, via our camera, that she remained on the nest - incubation had begun. It must be increased, prolonged temperature increase brought about by her sitting on the nest that kick starts the development of the embryos within the eggs.

Incubation

In the UK you cannot in normal circumstances disturb or take any eggs from any wild bird nests. The circumstances which allow for it, and who can do it, are very limited indeed to protect wild birds in the UK. You should make yourself aware of any relevant legislation and act accordingly.

The literature (websites) told us about 28 days is the period incubation period before eggs start hatching. We did have a limited time to study 'natural' incubation by Jemima before she was sadly killed by the fox.

While she was with us we noticed that she did not stay on the nest 24/7. Though she stayed all night (unless disturbed) she would disappear first thing in the morning for an hour or so and then again in the afternoon before returning to sit on her eggs. Occasionally ferreting around in the eggs, probably turning then and moving them round in the nest.

Jemima's first night on her eggs

Down in nest increasing

It was interesting that in Jemima's case she didn't appear to start lining / adding feathers to her nest until after she started incubating. As the days past you could see the layer of feathers, plucked from her own chest, grow round her. She was slowly engulfing herself in her own feathers before she was killed.

The purpose of her time away from the nest may have been for a bit of rest and recreation with her partner and to wet her feathers. Quite a few times both her and her drake would return to land in the pond before she resumed her duties, the drake would then almost immediately fly off again.

Sometimes she returned to the nest site followed by other drakes from her breeding partner. At this time apparently the unattached drakes will try to mate with hens. Jemima would do all she could to avoid the new drakes and acted quite differently to them than when she was with her own breeding partner. She would go to extraordinary lengths to try and 'loose' him, sneaking round the garden, flying off and returning, slinking low in the undergrowth to try and return to her nest. I think that had she led him to the nest her existing eggs may not have survived the resultant trampling of the drake / hen encounter.

We did read somewhere that one of the purposes of her partner hanging around, apart from mating again for a replacement clutch, was to protect the hen from these errant drakes. We didn't see this in our garden, whether it happened on the pond/ river/canal that Jemima went to during the day we don't know.

First 'pip' mark

Jemima hiding from her foe

I say she was wetting her feathers, and this was because of the things we read when we had to incubate the eggs ourselves to stop the ducklings becoming 'shrink-wrapped' in the shell membrane. We manually wet the eggs and tried to control the humidity, and temperature, water containers and light buds in the incubation box. Mother nature manages this quite satisfactorily apparently with wet feathers and a sitting duck.

We read a lot of stuff about how time away from the nest or allowing the temperature to drop outside a range (if you were incubating eggs yourself) would render the egg non-viable or slower in hatching. While Jemima was with us she would leave the eggs daily, while incubating, for periods of 2 - 4 hours. She even left the nest when disturbed by a cat of 9- 10 hours on the coldest April night on record in the UK. There were other extended periods of absence while she was trying to avoid the unwanted attentions of amorous drakes that followed her back to the nest area. We were a bit paranoid when we took over incubation and trying to get things right.

I suppose one of the reasons ducks have lots of eggs is to account for loses like this as well as high duckling mortality in the first few weeks. However, in our case all 14 successfully hatched.

Transfer to the brooding box 10 am 24th April 2021

Eating my veg 7:48pm 12th May 20211

Hatching

It's worth another warning here - if you are planning to hatch and raise Mallards yourself THINK VERY CAREFULLY before you start. It's basically almost a full-time job for 3 months. It's not fair to you or your foundlings if you have not the time, energy, resources, and dedication to finish the task you start properly.

If in the UK, you should also bear in mind that any wild Mallard hatched must be released back into the wild within a certain time frame.

27 days after she started staying on her nest overnight, we started seeing the signs of hatching - the first 'pip' marks. It was 24 hours later that the first duckling hatched - 28 days after Jemima started full time nest sitting. The first hatching was in the middle of the night.

In the wild they say hatching takes place over 24 hours. Ours was a more protracted affair over a couple of days. This may well have been due to the variability of temperature across the eggs while in our care or because of Jemima's absences from the nest.

Various websites say the hen and ducklings stay together in the nest so the ducklings can dry off for about 10 hours and then the other moves them on to the water. Certainly, when we came across Jemima and her surprise brood in 2020, they were resting under an apple tree after jumping down from the wall, she then led them from one pond to another in our garden, however she did always try to lead them out of the garden. In her head she obviously knew which way to take them, it's just not so easy by foot as flying!

Feeding ramp 12:55pm 28th April 2021

Feeding

Ducklings can feed by themselves straight away. Their mother doesn't have to feed them. You do read that the ducklings don't eat for 24 hours because they live of the yolk they have adsorbed from the egg. Our ducks seemed to eat ground duck pellets, crushed oats and drink water as soon as they dried off. Mallards are omnivores and eat a variety of food, of both plant and animal origin.

More peas happily received 11:36am 11th May 2021

Depending on what you read ducklings primarily eat insects to start off. I have to say from the start outside they were game for anything that would fit in their mouth and could swallow, animal or vegetable. I think they just must learn what is edible. This included insects, worms, slugs, snails, frogs, and fish.

In our case we started them on ground duck pellets and crushed oats in water, squashed peas, fresh cut grass and dandelion leaves and stems (all chopped up) till we ordered some Baby Chick Crumb (Complete Dry) from Allen & Page through Amazon and added that to their diet for a short while. At the same time the ducks eat what they pleased out of the ponds and garden.

There is plenty advice out there what to feed ducklings, and if you are giving them food you must make sure it has the right balance of supplements to prevent development of abnormalities such as 'Angel wings'. Once the chick crumb (5Kg!) had run out we moved them on to Goose/Duck Grower Finisher (again from Allen & Page through Amazon) to supplement what they scavenged themselves.

Our ducklings carried on with the crushed oats for a few weeks but then started to leave it so we stopped giving it to them. Peas were always a favourite of theirs even in their last week with us. At night while in the shed we always made sure they had fresh cut grass, dandelion leaves and stems and clover.

In the last couple of weeks we brought some wheat to mix in with the other food. They were initially reluctant to eat it but more and more disappeared as time went on.

Duck Development

Ducklings seem to grow rapidly by the day. Watching their body shape and colour change, which feather grow first in which areas of the body was fascinating.

At the start of our adventure, and even during, we knew very little about duck anatomy and physiology. To be honest I don't think you need to know a lot apart from knowing how to handle and feed them and also what to watch out for to keep them safe.

However, as they grow you do get a bit curious about what all the parts you see are. As a result, and all the pictures we had, I did make a little video to remind me - and give me some happy memories.

Feather development and feather patterns

The way the feathers developed at different speeds on different parts of the body at different times fascinated me. We avoided handling the ducklings whenever possible and never picked them up to examine them, only to catch or move them quickly and carefully so we didn't have the opportunity to look in more detail. I think it would have been quite distressing for them, and unfair, to put them through it just to satisfy our curiosity. Instead, I resorted to taking daily pictures of them during their activities with the hope I could catch the changes, though I have to say they were not always the most co-operative models. Another little video puts together some of these pictures to try and show the pattern and order of development.

When hatched mallard duckling's are like bundles of yellow and brown downy feathers with two dark feet at one end and a dark bill at the other. As the days pass the chest seems to develop and start to stick out.

The first few weeks see the most profound visual changes in duck size, shape and plumage. During the first week though small in size, you start to see the tail feathers (rectrices) start to push out in length, hardly noticeable at first but starting to catch your attention as the days pass, sometimes looking like little peacock feathers.

The white or the pink? 4:54pm 11th May 2021

Standing proud 2:39pm 17th May 2021

During week 2 the breast feathers seem to start to develop, and suddenly on Donald (the largest) we noticed 'proper' feathers start to appear on his shoulders (the scapular feathers). His patch of feathers grew bigger by the day and his siblings rapidly followed him. By the third week feathers started growing on their flanks and bellies.

During the week 4 we noticed a flash of blue on one of the Donald's wings and thought it must be the speculum starting to develop (we didn't know it was called a speculum then - it was just a blue band to us then), but we were a bit premature, it was the start of the primary wing 'pin' feathers starting to grow out, encased in an ever-growing blue sheath. It was fascinating watching them grow in length and feathers 'pop' out as the sheath was pecked or worn away.

Further up the wing we started to see the white tips of the secondary feathers appear, easing out to reveal the black underneath. I have to say we then got a bit confused as we expected the blue band to appear, not realising at the time that the speculum is made of a nesting, or layers, of feathers. First are the secondary feathers, tipped with white, then black with blue below. Above them are the secondary 'covert' feathers. These form the lower black and white band of the speculum.

Look at these for size 3:59pm 17th May 2021

I will try harder 12:59pm 22nd May 2021

Flapping 11:45am 28th May 2021

I want to be a conductor 5:24pm 31st May 2021

What we were seeing was the emergence of the black tips of the secondary covert feathers. We only understood this as we saw the first 'blink' of blue on the secondary feathers as they grew out faster than the covert feathers. It's amazing what you learn when you investigate the things you see.

First sign of the Blue Speculum 3:51pm 3rd June 2021

Green colour starting to appear 4:57pm 25th May 2021

By this time the breast, flank, belly, and underbelly feathers all seem to have developed, they are all starting to look like proper little ducks, albeit all female looking with just traces of downy feathers. It was only at this point we released what a wonderful flowing shape all these feathers formed together, a good aid to swimming through water. It also became clear to us then (though I am sure all avid duck enthusiasts and bird watchers already know) that the wings also nestle down behind the flank feathers when they are folded back on the body. This again keeps then lines clean for water flowing around the duck while swimming over water.

You could also start to notice flecks of green appearing on the head. At first we thought these must be males, but I think we were wrong on that score as they ALL started to have these little green flecks.

Another intriguing observation was the pin feathers halfway down the wings, we had not really thought about wing structures - other than birds flap them and they go up! It was only after looking at some of the pictures I took while they were flying that we realised what most bird watchers already know - the existence of the 'Bastard wing' or alula. This structure helps create lift for the bird and prevents 'stalling' when a bird comes in for landing.

Aula or 'Bastard Wing'

Male (Drake) and Female (Hen) bill colour - adolescents

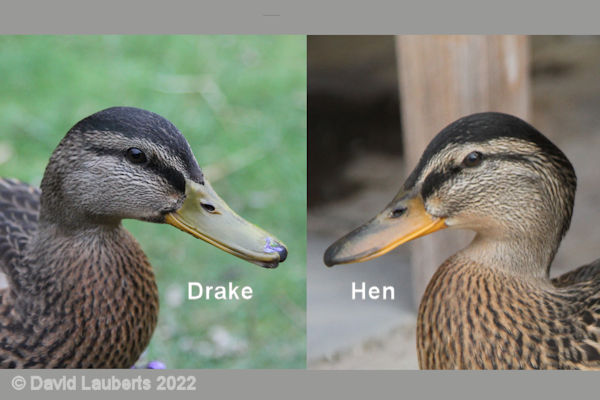

With our ducks starting to look like ducks now we were always looking for ways to tell the females from the males. You can read a lot a stuff about head colours and legs, quack or no quack, type of quack, but it never really worked for us, the nearest we think we got was in the 5th week when we noticed the bill colours changing into 2 distinct types.

Though we were never actually able to confirm it (we never saw them develop after they flew away) we think at this point the males' bills started to take on a green (some people say yellow, but ours where definitely more of a green), while the females bills took an orange / brown colour. The wings stated to become more spectacular with the blue of the speculums starting to emerge.

We did read some American articles online about determining the gender of Mallards by looking at the lower white line on the speculum and how far it extends inwards towards the body. Apparently in males it ends when the speculum, but in females it extends onto the tertial feathers.

A little Angel! 5:39pm 14th June 2021

We didn't read this till after the ducks had flown so could only look at it in videos and pictures and never really saw any conclusive proof of that. We saw the line extending in some, but it didn't tie in really with the bill colouring in some cases.

Week 6 saw most of the primary and secondary pin feathers fully developed and the bright blue speculums in their full glory. It was in trying to watch these develop that we noticed that the ducks fold their wings back beneath the flank feathers, the bright speculum hidden from view by the drab, brown flank, tertial and scapular feathers (camouflage?), but also for more efficient swimming.

The last feathers to start to develop and emerge seem to be the underwing feathers or coverts. Their amazing white colouring contrasting sharply with browny belly and chest colouring. Before the ducks I never really appreciated that birds had underwing feathers.

Underwing feathers must have a purpose or they wouldn't be there, The classical response to the purpose of covert feathers to act as cover or 'contour' feathers, not flight feathers, giving a good aerodynamic shape for controlling and shaping airflow under the wing.

I do ponder on why they are white though. I assume it's a camouflage of sorts and must be similar to that of the light colouring under ye old combat planes - in this case to make them less visible from predatory birds looking up from beneath.

Flying

Wing flapping, as such, starts almost immediately. You can see them start to try and stand tall and stretch their little arms with in the first 2 weeks.

As the weeks pass and their wing feathers develop this gets more and more pronounced and more frequent. Flapping / exercise occurs both on land and water though it becomes more prolonged and practice flying, for us anyway, when out the water.

Our lives were to change again in the next weeks as the these beating wings grew in size and strength and our little wards grew ever more independent and freer.

The first 'flight' we saw was during the week 7, a matter of a couple of meters. At this point all the feathers seemed developed apart form a few underwing feathers, still half wrapped in their sheaths. It was interesting that they rapidly seemed to tire from trying to fly, we could perhaps encourage them to try once or twice during the day, but mostly after an early morning effort they were more interested in what's for breakfast, lunch and dinner and having a kip.

Sweeping the skies 9:16am 30th June 2021

The distance, height and number of birds achieving this increased rapidly. We have quite a large garden, but it's not really big enough for ducks practicing longer flying stints.

The first 'proper' flight (to our next-door neighbour) was a week later at 8 weeks. However, once they had flown over the fence, they wanted to walk back rather than fly. The nature of urban UK gardens with fences is not really suited to this stage of duck flight lessons.

By the end of week 8 several could do extended flights to leave for pastures new.

In this period we 'escorted' or carried a few ducks back that had flown over onto nearby roads or into gardens, but of those who 'disappeared' into the distance we assumed could fly well enough to get back if they choose to.

The remaining ones, bar Baby, all departed by the end of week 9.